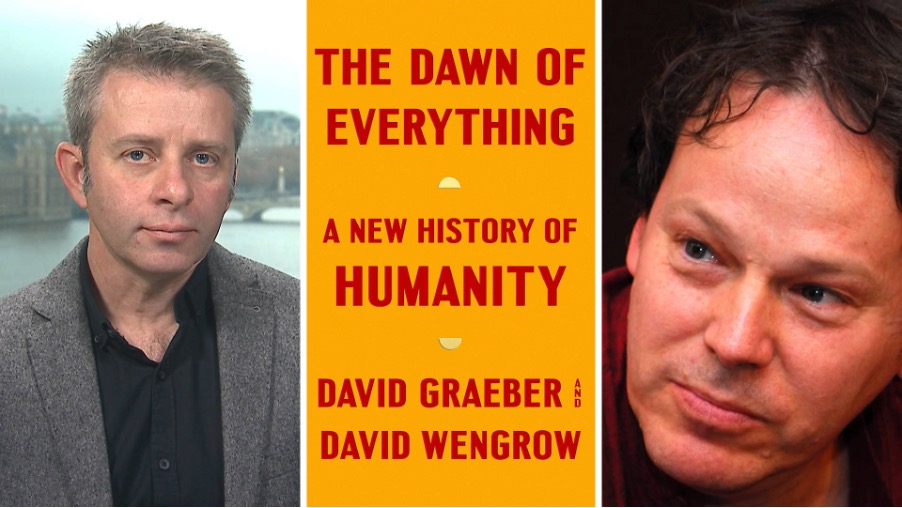

Don’t you love it when preconceptions get overturned? Traditional anthropological theory, based on archaeological remains, assumes that humankind during the Paleolithic (15,000-35,000 BCE) lived in small forager bands – the definitive hunter-gatherer. But recent evidence of ornate princely burials and monumental architecture means we have to do away with preconceptions of such ‘primitive’ societies, argue Graeber and Wengrow in their extraordinary book The Dawn of Everything.

It’s commonplace to hear the latest business book hailed as ‘groundbreaking.’ But not by the brilliant economist Rebecca Solnit (Doughnut Economics) who describes The Dawn of Everything ‘the radical revision of everything’ because – well – it is! It’s not a business book as such, but, as its subtitle says, ‘A New History of Humanity.’ The authors argue that we should think of ‘primitive’ people as being more like us than less. It is surprising to learn that they did business in ways we would recognise; it is flabbergasting to find out that they were likely very well-led.

In 1944 Claude Lévi-Strauss published an essay about politics among the Nambikwara, who until then had been regarded as typifying the Paleolithic – simple folk living in a rudimentary egalitarian culture. Not so, argued Lévi-Strauss. For all that they were averse to competition, they appointed chiefs to lead them. These chiefs, he argued, were people who ‘unlike most of their companions, enjoy prestige for its own sake, feel a strong appeal to responsibility, and to whom the burden of public affairs brings its own reward.’

Sound familiar? The Nambikwara, who have always lived in northwest Mato Grosso, Brazil, appointed their leaders to broker between two entirely different social and ethical systems. During the rainy season they ‘occupied hilltop villages of several hundred people and practised horticulture; during the rest of the year they dispersed into small foraging bands. Chiefs made or lost their reputations by acting as heroic leaders during the ‘nomadic adventures’ of the dry season, during which they typically gave orders, resolved crises and behaved in what would at any other time be regarded an unacceptably authoritarian manner; in the wet season…they employed only gentle persuasion and led by example…and never imposed anything on anyone.’ (The Dawn of Everything pp 99-100)

In other words, the leaders of the Nambikwara now and likely 350 centuries ago (!) displayed the leadership insight, flexibility, intelligence and empathy to combine two completely different models of leadership, to be effective in two radically different environments. In doing so they destroyed the conventional thinking of the evolutionary anthropologist by moving between hunter to forager to farmer and back again.

How many modern leaders are as sophisticated as the prehistoric Nambikwara?